- Home

- Lucie B. Amundsen

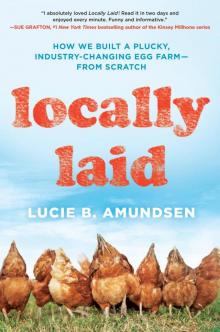

Locally Laid

Locally Laid Read online

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright © 2016 by Lucie B. Amundsen

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Most Avery books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs. Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write [email protected].

eBook ISBN: 978-0-698-40405-2

Some of the names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Version_1

To Jason, Abbie, and Milo

for giving me

a storied life

All photos were taken at Locally Laid Egg Farm in Wrenshall, Minnesota.

Contents

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

Act 1: Hatch

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

Act 2: Cluck!

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

Act 3: Egged

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

Act 4: Pecked

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

Act 5: Fledged

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

ACT 1

Hatch

VERB: to emerge from incubation; to conspire to devise a plot

Chapter 1

2012

At dusk, hens seek their coop. So reliable is this, there’s even a saying, an adage: Chickens come home to roost. It’s for warmth. It’s for protection. It’s hardwired. But our first shipment of nine hundred mature birds, just purchased from a commercial operation, stands on the field staring. They tilt and turn their heads to better align us with their side-placed eyes, as though awaiting instructions.

Then, as darkness quiets the pasture, I get it.

My hand on my lips, I mumble, “Oh, God.”

These hens are out of sync with sunset because until today, they have NEVER SEEN THE SUN. While I’ve worried about many things going wrong with our unlikely egg startup, CHICKENS not knowing HOW TO BE CHICKENS was not one of them.

2010

Two summers before I’d ever heard the term pasture-raised, handled a mature hen, or imagined our egg cartons in grocery stores, my husband and I were enjoying a rare weekend alone. Our school-aged children were trooped off to his mother’s town house in the Twin Cities. I can’t remember what our children were doing in Minneapolis that weekend, but likely they spent time in their grandmother’s community pool. The weather was perfect for it.

Even up in northern Minnesota it was hot, hotter than we’ve come to expect for this not-quite-summer month in Duluth. Spring is slow to come here. For perspective, my lilac bushes don’t pop a blossom until midway through June. We’re still scraping our cars while friends’ flower beds just hours south in the Twin Cities look like a Georgia O’Keeffe painting in heat.

But this particular June day in the Northland, I wanted nothing more than to be outside. I set about tucking fragrant petunias and tall grasses into the large planter at our home’s front door, while Jason made another go at his chicken coop project, behind the garage. I couldn’t see him, but the banging and swearing wafted over.

One could say this was my fault.

Late the summer before, I’d written a story about Duluth’s new poultry-friendly city ordinance. Lots of communities have something like this now. In fact, five hens allowed in town is so commonplace it’s practically a non-story, but in 2010 Duluth was an early adopter in the urban farm movement. And Jason was unexpectedly spun up in its “grow your own food” zeitgeist. Until then he’d shown little interest in keeping a vegetable garden, or even in lawn care. But after my article hit newsstands, he’d piloted our Toyota minivan to a flea market just over the bridge to Wisconsin. He’d returned with several sheets of corrugated metal and a good-sized domed skylight strapped to the rack. The window had been rejected from a Walmart construction site for a hairline crack; Jason felt it was nothing a little duct tape couldn’t handle.

The following spring, with at least one complete teardown and do-over, the result was a home chicken coop that looked a bit like a handicap-accessible Porta-Potty. And though he’d had significant help from our neighboring carpenter, Matt, it wasn’t a bad attempt for a man who’d never so much as built a bird feeder.

Jason had been actively working on it since early spring and though it was not yet complete, we’d long had chicks. Seeing the fluffy baby birds at the feed store that early spring, he hadn’t been able to restrain himself, coming home with five little peepers—their coop home barely even begun. During the construction period, they lived in our garage.

Like all our pets, the chicks immediately bonded with Jason, scrambling to him in our urban yard when they heard his voice. Soon they’d outgrown their kiddie pool home where they’d chirped nonstop under a heat lamp, all fluff and peep. Now they were deep into their awkward adolescence: beaks growing faster than faces, feathers sprouting over down, and legs rapidly outstretching coordination. It’s a universally cruel stage.

The hens, now uncontainable tweens, freely roamed our garage at night, defecating indiscriminately. I tried to be a good sport as I wiped their brown-and-white poo dollops from my Christmas storage bins, deciding that seeing Jason buoyed by these birds was worth a certain amount of shit on a box.

The chickens spent their days in our mostly fenced-in yard, walking about with their jaunty, robotic manner while absurdly chattering on—CO-KE … coke coke coke coke. They murmured pleasantly, scratching the earth hunting for bugs and seeds while Jason stood by, beaming like he’d hatched them himself. To be fair, I also felt a sense of secondhand joy as I watched a hen open her wings forward, beak into the air, and stretch back a single leg into what we called the chicken yoga pose. That’s a happy bird.

And I saw that these chicks meant more than just the promise of fresh eggs. For Jason, it was a step toward modest self-sufficiency. While we both come from a line of people who can damn near fix anything, we cannot. I tease that we’re remedial adults and while I don’t like that feeling of helplessness, Jason was actually doing something about his deficits. He was working the poultry angle as an independent study toward his life skills GED. Overall, it’d been good. This self-directed project, worthy of a 4-H ribbon, had renewed his confidence and brought him hands-on satisfaction, something that his office life managing grants at a politically charged hospital behemoth did not.

Just the week before, while digging beetles out of the garden to hand-feed “the ladies,” he’d prattled on about how things “were really turning around for us.” In some ways, he was right. We’d recently bought a house with a modest view of Lake Superior and moved out of an awkward rental situation. And because our new house has a little motherin-law apartment, we’d rented

out to a college student, and our cash flow was trending positively.

But, to be fair, Jason often feels that happy pull of life’s pivotal turn. For him, we’re always a heartbeat away from that elusive place where everything will come together.

“It’s all right around the corner,” he assured.

I nodded. Despite my suspicions that we actually existed in a round room.

On my knees at the planter, a shadow cast over me.

“Lu,” Jason said, and I looked up. Dirty in his red ball cap and leather gloves, he was charming, like a boy playing farmer. “We should go out for Mexican. Just me and my Bird.”

This delighted me.

Married for almost a decade, I love that he still calls me that.

Nearly every boyfriend I’d ever had has called me Bird. The consensus is accidental, but no doubt the endearment is appearance based. Not only did I inherit my father’s nose, a thoroughly unapologetic appendage, I got it to exact scale.

There’s an upswing, though: my “nose advantage.” As surely as it has protected me from shallow men, it’s also made me work harder, foster a sense of humor, and, perhaps, be a little kinder. It was obvious at a young age; I wasn’t going to make it on my unique beauty alone.

So when I hear the tenderness with which Jason calls me Bird, it feels like a little love song from someone who’s passed a test of character. It’s my silver lining to a life bereft of the normal use and enjoyment of champagne flutes and shot glasses.

I smiled. We were going on a date.

Showered and changed into one of my favorite summer flirty skirts, I enjoyed the happy buzz from the day’s sun, the cold beer, and the warm chips. Even the loud chatter of Mexico Lindo patrons, which can sometimes jostle my nerves, seemed pleasant that night. It was a warm gift of an evening after a beautifully productive day. And that was when Jason said what every girl out with her fella longs to hear.

“I want to talk to you about something,” he said, clearing his throat. “Commercial egg farming.”

If this were a sitcom, a record needle would scratch across vinyl and someone would cue the laugh track. But as this was just my life, I blinked and kept shoveling salsa into my mouth between gulps of beer. Buzzed on Corona and that special hopeful feeling a woman gets about her man, I dodged.

“Yeah, well, I really like the chicks, too,” I said, not looking up. “Mmm … I gotta stop with the chips, but this salsa is so fresh.”

“Lu,” Jason pushed on, “I’ve read these books on raising chickens on pasture, Joel Salatin books …”

I vaguely recalled the name. Wasn’t he in Omnivore’s Dilemma or maybe one of those disturbing food movies?

“Chickens on pasture … like free-range eggs?” I offered.

Instinctually, I knew he wasn’t talking about whatever cage-free eggs are. While I wasn’t then sure what the exact distinction entailed, I’d been a writer long enough to sense something too careful in the phrasing “cage-free” to convince me those birds were out frolicking in the fresh air.

“No, this is much better than that,” he said with a hint of annoyance. He explained that free-range chickens (using cheeky air quotes to emphasize the term) often go out into the same field day after day until it’s pecked down to nothing but dirt, hardpan. That is, if they actually go out at all. It’s one of those terms that’s been co-opted by marketers and can now mean a warehouse packed with tens of thousands of birds and just a few small doors leading to an outdoor concrete patio.

“Pasture-raised birds,” he said proudly, “are rotated onto fresh grass every few days, so the field is actually part of their diet. It reduces food costs, plus the hens get exercise and so are, you know, better for it. Their eggs, too.”

Jason prattled on about how some 95 percent of America’s chickens are in battery cages—that’s a poultry housing system made up of neatly lined wire crates. With several chickens in each cage, it allows for hundreds of thousands of birds stacked in a single building.

Then he moved on to the subject of cage-free birds. While an improvement, these chickens wander freely around their warehouse, but with no access to the outside world or even natural light.

“They’re not in cages, but they can never leave—so it’s like one big cage.”

“A little like Hotel California?” I offered, but Jason did not acknowledge my vintage Eagles joke.

That left the category of pasture-raised chickens. It seems they’re living the poultry dream—and, according to Jason, we could be, too.

I nodded as I took another swallow of beer. I didn’t say that it sounded like an enormous amount of work or that we live in arguably one of the harshest climates in the continental United States. Nor did I point out that having spent our entire careers jockeying keyboards to make a living, we are not farmers.

So while I didn’t exactly tune him out, I became a passive listener. A very passive listener. Poultry wasn’t exactly the foreplay talk I was hoping for, so instead I just enjoyed the rhythm and cadence of his voice. I heard something about pastured hens foraging on fresh grasses producing healthier, delicious eggs with less fat and cholesterol, something about the local food movement and its ability to remake America’s food system.

I signaled the server for a second beer and let it all wash over me with an occasional nod until an utterly un-ignorable statement pulled me out.

“This is the kind of farm I want to start,” he said.

Now I was listening. In fact, I was listening so hard I realized that this particular corner of the restaurant was a convergence point for the piped-in music from two separate rooms, and they were competing against each other like dueling mariachi bands. Across from me, Jason was searching my face for traces of excitement about his decision to answer the noble poultry calling.

Start a farm? I thought. This is a man who until a few years ago could not identify a pear.

I swallowed, understanding I would have to steer hard and fight inertia to keep this date on track.

“Jay, honey, let’s just be happy right here, right now. I mean, we’re living in Duluth like you wanted. We’ve finally got real health insurance, and the kids have adjusted well.”

“Lucie,” he said with clear exasperation, “this is so much bigger than that.”

Had I not been listening when he used “Itsy Bitsy Spider”–like hand gestures illustrating the sun nourishing the grass, which shelters the breeding insects that augments the pasture diet of the grazing and exercising birds, making for superior eggs?

I got irked and defensive. Not that he believed I hadn’t followed the ecological circle of life he’d demonstrated, but rather defensive of the life we’d built.

“Listen, Jason, for like two goddamn minutes can’t we just BE without chasing some … elusive something else?”

This was louder than I intended and the couple sitting next to us eyed me. I gave them the “everything is under control here” sheepish and apologetic smile-nod, and I felt our beautiful evening bank and careen off course.

I cleared my throat, took a breath, found a gentle smile somewhere in my increasingly tense body.

“You have chickens now and the coop is coming along great,” I offered as kindly as I can. “Why not do that for a while? See if you like it?”

“No, this is more than a backyard flock; you don’t understand how this could change our lives.” Jason’s gaze was now intense.

Oh, but I did understand.

I understood that we’d make big-ass fools of ourselves and probably lose everything in the process. Jason leaping into agriculture with a poli sci degree, a master’s in international affairs, and five pubescent chickens shitting in our townie garage is the working definition of asinine. The word’s got ass right in it.

“All right”—my thoughts scrambled as I became aware of my breathing—“but you’re not saying you’re going to leave your job to be a chicken farmer, right?” I said it with forced lightness, a softball statement meant to be disputed.

“Well, I wouldn’t quit right away—but yeah,” he said. “I want to build a local egg-laying business … with cattle, too.”

No hedging, no sugarcoated vacillation. There it lay, like a turd on the table between us. Hopeful mirth packed her little bags and left the room. My beer glass came down too hard and the concerned couple next to us looked up again. But I was done with niceties. Soon, they were flagging the server for the check.

“Lu, it’s a perfect system,” he said, continuing on about people wanting to feel connected to their food, as I crossed my arms and legs and adjusted my weight in an annoyed cant at the back of the chair. As he talked, all I could hear was the rush of blood through my ears. I was still stuck on cows.

My mind flashed to the ag majors in my dorm at the University of Maine, a land-grant university outside Bangor. They wore tall muddy boots and had long rubber gloves that went past their elbows for exploring a cow’s nether regions. Jason didn’t own gloves like that. And something about the concreteness of that fact fueled my outburst.

“Jason, you are NOT a farmer. You’re a guy who had an idyllic youth in a wealthy suburb,” I said, leaning in with a sharp edge. “You have pushed me on too many major life changes to pursue ambitions—YOUR ambitions.” I thought of how I’ve contorted to accommodate his varying and ever-changing pursuits.

My voice pushed higher as I went on.

“I moved to this godforsaken Arctic for you. Because you told me … you told me it would make you HAPPY!”

On that last part, I thought I might reach across the table and snap Jason’s head off.

We’re not a couple who fights and certainly not in public. And usually, if I push back on something, Jason can be counted on to put his crazy notion du jour into a holding pattern, to think it through a little more and, over time, see reason to abandon it. Ideas that have died this way include but are not limited to the following: opening a wind turbine collective, starting a hedge fund, and buying a sailboat to transport goods via Lake Superior. (The fact that I’m a rail-hanging vomiter on open water probably helped nix that one.)

Locally Laid

Locally Laid